Hypst is an early stage startup - the elevator pitch is "like Facebook, before it became mainstream". The founders of Hypst have read a lot about A/B testing and statistics, and they decide to use the techniques they learned to improve engagement.

The first thing they notice is that not enough people are inviting their cool friends. So they come up with alternate captions, and discover that "invite only your cool friends" achieves 20% more invitations than "invite your buddies". They commit this version to master and continue. Then they notice that no one is clicking on their "liked it before it was cool" button. They come up with alternate designs, run an A/B test, and discover that a green button achieves 20% more clicks than a blue one. The third thing they notice is that people don't engage with the Irony Feed. They tweak their algorithm, run another A/B test, and discover that a wider Irony Feed gets 20% more clicks than the original design.

All their tests were run with proper statistical methods and clean experiment design. All the aforementioned test results were statistically valid. Yet somehow, after running these three tests and implementing the best version, they observe that clicks are down 2.8% across all categories. WTF just happened?

In the first test, they increased invitations by 20%. They also reduced clicks on the "liked it before it was cool" button and the "irony feed" by 10%. Since the goal was to increase invitations, they went ahead.

In the second test, they increased Likes by 20%, but reduced clicks on invitations and irony by 10%. Since the goal was increasing Likes, they implemented the change.

In the third test, they increased clicks on the feed by 20%, and again reduced clicks on the other two parts of the site by 10%.

The net result is that each part of the site experienced a 20% improvement and 2 10% decreases - 120% x 90% x 90% = 97.2%, a 2.8% drop in overall engagement. It's a bit ironic that 3 good decision processes together lead to a bad decision.

What Hypst needed was an objective function - a single number to represent how close they are to their overall goal, and which they use to make all decisions.

Who should read this: My original plan was to write a single blog post about how to come up with good metrics. After it swelled to thousands of words, I decided to break it up. This post deals solely with what an objective function is and why you need one. If you are already convinced of this point, skip this post.

Objective Functions

Mathematical optimization is the field of study devoted to the following problem:

Given a function

m(x), find the value ofxwhich makesm(x)as large as possible.

The function m(x) is called your objective function.

In real world terms, m(x) is a success metric for your organization or process. It should be designed so that whenever you choose an x which makes m(x) larger, the outcome of your organization is improved. I'll use the terms "metric" and "objective function" interchangeably.

For example, at a for-profit company the obvious choice of m(x) would be profit, and x would be the set of states of the world. The goal is then to choose actions the company can take which will cause the resulting input x to maximize m(x) (which can be constrained to exclude some actions, such as "don't be evil" in the case of Google).

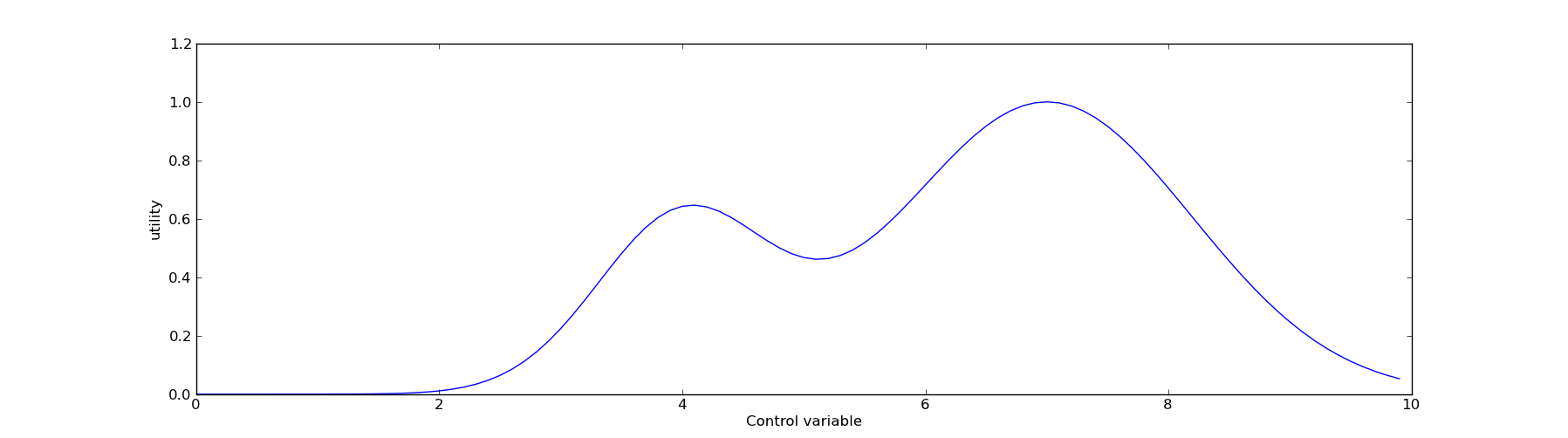

A picture is worth a thousand words, so here is our first picture:

The x axis represents a control variable - think of it as representing a state of the world (e.g., a world in which we give a patient x mg of a drug). The y value represents our objective function, or how much we value the outcome given a choice of x. Given two different values of x, we can always choose which one we prefer - we always prefer the x value for which the corresponding y value is greater.

In practice, we obviously cannot always choose arbitrary x. Some world states might be inaccessible - I don't know how to move to a world state where my bank account has $20B in it, for example. Sometimes you don't know which world state your actions will cause you to switch to. These are important issues, but they are a topic for another post. None of these issues change the fact that you need an objective function on world states - they just create further difficulty when you try to optimize it.

A metric is equivalent to a consistent decision making process

A common critique of metric-driven decision making is that "you can't reduce the whole world down to a single number". This philosophy is simply incorrect. I will assert that any consistent and complete decision making process is fundamentally identical to a metric.

Suppose you have a decision making process. What I mean by this is that you can, given any two scenarios, decide which scenario is more desirable. Suppose further that this process is transitive, which means that if A is preferable to B and state B is preferable to C, then A is preferable to C. In that case, you can construct a well defined mapping from world states to numbers - this is an exercise in elementary topology.

To understand this example, consider a world with three states:

[A,B,C]

Suppose we consider C the best, B second best and A worst. In that case, a valid metric would be:

m = { "A" : 1, "B" : 2, "C" : 3 }

Another equally valid metric would be:

m = { "A" : 100, "B" : 1000000, "C" : 1e27 }

The numbers here don't actually matter - all that matters is the relative ordering.

This vague idea can always be extended. (Skip this paragraph if you find it too mathy.) Consider another element in the state space, perhaps X. Consider the set of all elements in state space to which we've already assigned a value, and divide them into elements inferior to X (call this set LT), and elements superior to X (call this set GT). Then set the value of m(X) equal to 0.5 * ( max(LT) + MIN(GT)). Apply induction and you find you have a metric on a countably infinite set. (Note that I just used the axiom of choice.) This shows that a consistent decision making process is always equivalent to a metric on countably infinite sets.

The key idea here: an objective function is nothing more than a convenient way to rank which world states you consider more desirable. If you consider Bipasha Basu to be more beautiful than Megan Fox, m(girlfriend == Bipasha Basu) > m(girlfriend == Megan Fox). If you felt the opposite, the inequality should be reversed. Don't be fooled by the presence of mathematics - this is a very simple idea.

Understand your tradeoffs

The critical part of defining an objective function is figuring out what your tradeoffs are. In an educational setting, we want students to understand both mathematics and English. In a world of limited resources, we cannot improve both of these skills as much a we might like. At some point, we must answer the question: "how much math skill will we give up to gain a unit of English skill?"

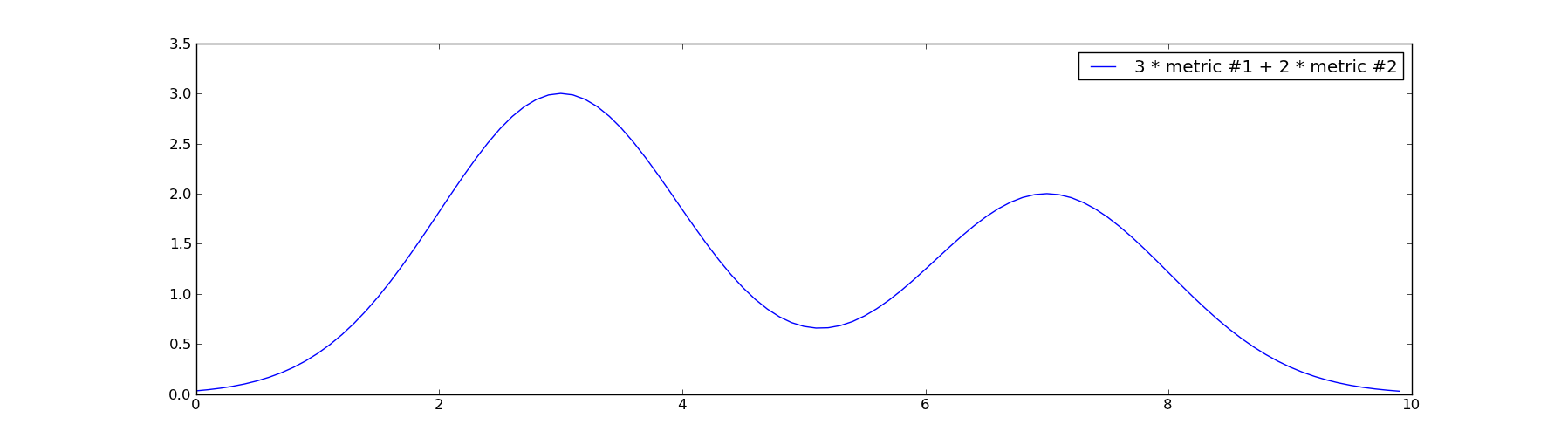

If we define the metric as 3 * math + 2 * english (assuming math and english both vary from 1 to 10), we are explicitly stating that we will give up 3 units of english for every 2 units of math we might gain (or vice versa).

You can't have everything. If you can't define how much you value one goal relative to another, you don't really understand what you want.

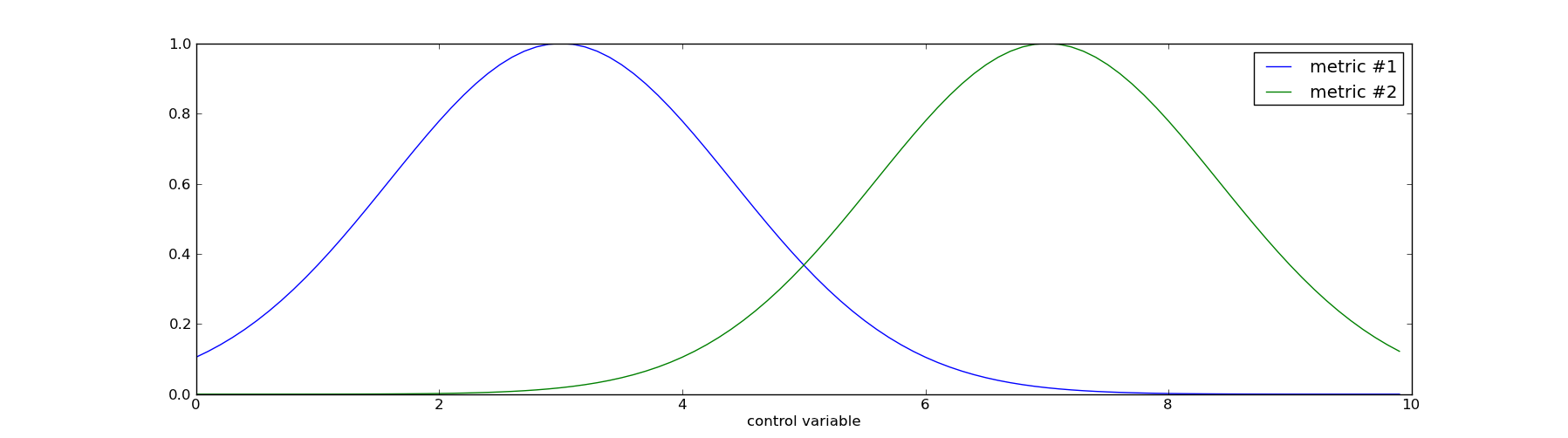

There can be only one

It is a fundamental fact of optimization that you can only have one objective function. You simply cannot simultaneously maximize two different functions, because the maxima of one might not be the maxima of the other. See the following graph:

This graph demonstrates the problem with having multiple metrics. By choosing x=3, we maximize the first one. By choosing x=7 we maximize the second one. They cannot both be simultaneously maximized.

Once a set of tradeoffs has been made, a decision is clear.

Coming up with a single, well defined metric is nothing more than the process of thinking clearly and deciding what you want. You don't know what you want until you know your objective function.

Inconsistent decisionmaking

Suppose you lack a metric, or equivalently a consistent decision making process. What this means is that the decisions you make are not necessarily consistent with each other, and you may become a Money Pump. A money pump is a theoretical construct by which you make a series of decisions that bring you back to where you started, but slightly poorer than before.

The real life risk of becoming a money pump is low, mainly because it requires a malicious actor to understand and exploit your preferences. However, there is a real life risk that your decisionmaking will be path-dependent.

Consider the following scenario (numerical example shamelessly ripped off from Eliezer Yudkowsky). You must choose between one of the two options:

A) 34% chance of winning $2,400.

B) 33% chance of winning $2,700.

Most people will choose option (B), as was demonstrated in an early economics experiment (see Allais, M. (1953). Le comportement de l'homme rationnel devant le risque: Critique des postulats et axiomes de l'ĂŠcole amĂŠricaine. Econometrica, 21, 503-46.).

Now consider the following alternate path, a sequence of two decisions:

W) Win $24 with certainty.

X) A 33/34 chance of winning $27.

Most people will choose (W) over (X). After this decision is made, you have the option of betting all your winnings from the previous decision:

Y) 34% chance of winning $100 for every $1 you put in.

Z) Don't bet, and keep your money.

Although I have no experimental evidence to back it up, I suspect most people would choose (Y) - your expected return from this gamble is 3,300%.

Here is where things get dicey - choosing (W) and then (Y) is equivalent to choosing (A).

In reality, either situation (A) or (B) is better - for simplicity I'll assume (B). But if you approach this choice via a different decisionmaking path, applying heuristics as you go, you will suboptimally choose (A) at least some of the time.

I.e., if your decisionmaking is inconsistent, it must be wrong at least some of the time. This is exactly what happened to Hypst - at least one of their design changes was bad.

Without getting into too much math, it is impossible for us to get into this situation if our decisions are driven by an objective function. Our objective function cares only about the state of the world, and not what choices you made to get there - i.e., m(A) = m(W -> Y), and m(B) = m(X -> Y). Thus, if we consider m(A) > m(B), we will also consider m(W -> Y) > m(X -> Y), and vice versa if m(B) > m(A). See here and here for more details.

What Hypst should have done

At the beginning of their testing program, Hypst should have decided what their overall goal is. All else held equal, it's always better to have more invitations, more clicks on the like button, and more interaction with the Irony Feed. But in the real world, all else was not held equal. In each experiment, one of these factors went up while the others went down.

What Hypst should have done was choose an objective function. The objective function represents their overall goals and tradeoffs.

For example, suppose Hypst values 1 invitation the same as 5 "I liked it before it was cool" clicks or 10 Irony Feed interactions. They might choose the objective function:

m = 10 x invitations + 2 x "like clicks" + 1 x ironic interactions

Now suppose they used this objective function for their tests.

The first test would have increased invitations by 20%, and reduced like clicks and ironic interactions by 10% each. Suppose that to begin, there were 20 invitations, 100 likes and 100 ironic interactions. To begin with, m=700. After the first test (the 20% improvement on the invitations), m would improve to 750.

The second test would increase likes by 20%, but reduce everything else by 10%. This would reduce the objective function from 750 to 729, leading the second modification to be rejected. That is because, as an early stage startup, Hypst values invitations a lot but likes considerably less. The increase in likes is just not worth the decrease in invitations.

Similarly, the modification (the wider Irony Feed) would increase ironic interactions by 20% but likes and invitations by 10%. This would reduce the objective function from 750 to 702, leading Hypst to reject the modified Irony feed as well.

At the end of the day Hypst has chosen to keep the "invite only your cool friends" button, but discard the green "liked it before it was cool" button and the wider Irony feed. As a result, they now have 20% more invitations, 10% fewer likes and 10% fewer ironic interactions. Because they value invitations more than likes and irony, this is considered a success - presumably Hypst is increasing it's user base.

That's considerably better than their previous decisionmaking procedure which resulted in a decrease in all categories. That's a clear failure.

Conclusion

The world is too complicated to reduce to a single number - this claim is not in dispute. Defining an objective function is not about reducing the world to a single number. It's about reducing your decision process to a single function (of potentially many inputs). It's nothing more than a way to keep yourself honest and consistent. It is only the first step in making good decisions, but it's an essential one.

In future posts I'll describe the properties of a good metric.