In a recent blog post, Panos Ipeirotis asks the following question (loosely paraphrased).

Consider a set of n oracles or mechanical turks, each with a probability q of returning an erroneous response. The capacity of a channel with error probability q is C(q,n), and information theoretic channel capacity is additive. So how can we use n low quality workers to simulate a single high quality worker with an error rate close to zero?

After some discussion in the comments of his blog post we reached a conclusion that this is a slight misrepresentation of information theory. Information theory traditionally deals with encoding an uncorrupted message and transmitting the coded message along a channel which might corrupt it. In contrast, in human computation (mechanical turk like settings), the original message is not available in uncorrupted form.

Basics of information theory

In information theory, one of our goals is to transmit information as efficiently as possible in a noisy channel. To set up the problem, consider a $@ k $@ bit message of the form

.

We wish to use additional bits of information to encode the message in such a way that random errors which flip a bit will be correctable. In formal mathematics, for some \(@l \> k\)@, we wish to find a function

with the property that for a sufficiently small number of errors, we can still reconstruct the original message.

The key concept in understanding error correcting codes is the notion of Hamming distance. I'll denote the Hamming distance between two messages $@ x, y $@ by $@ h(x,y) $@. The Hamming distance between any two messages is the number of bit flips necessary to transform one message into the other. Since errors in transmission are modelled as bit flips, the Hamming distance between two messages is a measure of how many errors need to be made before one might mistake message $@ x $@ for message $@ y $@.

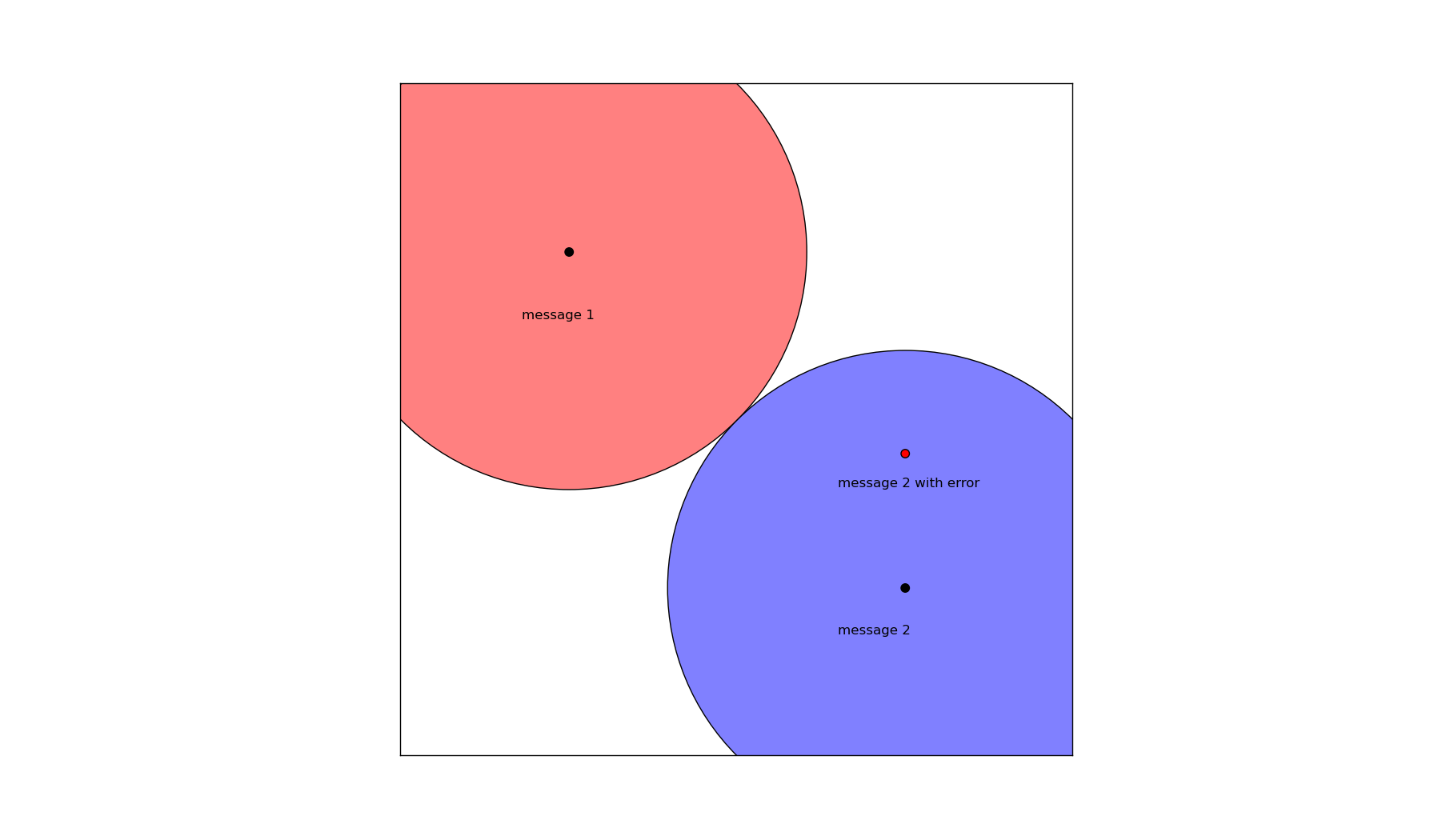

In pictures, the goal is something like this:

In this figure, we have two correctly encoded messages marked by the black dots. The red and blue circles represent the set of all messages with Hamming distance less than $@ d = (1/2) h(\textrm{message 1}, \textrm{message 2}) $@ from each of these messages.

As a result, consider now a small error which is made in the transmission of message 2. Because the error is small, the actual message received is shifted from it's true value (the black dot) to a new position (the red dot). But because the corrupted message still lies within the Hamming ball surrounding message 1, we can safely conclude that the message which was intended to be sent is message 2.

This is a simplification, but it gives the general idea of how error correcting codes work.

Hamming 7-4, an error correcting code

The Hamming 7-4 code takes a 4 byte binary message and uses 7 bytes to encode it. Specifically, the coding scheme is the following:

- Use bit positions $@ 2^i $@ as parity bits. The parity bit in position $@ 2^i $@ represents the parity of the bits for which bit positin $@ j $@ has the $@ i-th $@ bit position set. For the Hamming 7-4 code, this means parity bit 1 represents bits 1,3,5,7, parity bit 2 represents bits 2,3,6,7, and parity bit 3 represents bits 4-7.

- Use all other bit positions for the message.

Using this coding scheme, we have a function $@ f: \{0,1\}^4 \rightarrow \{0,1\}^7 $@ with the following property. It's fairly straightforward to show that for any pair of message $@ x \neq y \in \{0,1\}^4 $@,

.

This can be seen because if $@ x $@ and $@ y $@ differ by 1 bit, then at least two parity bits will differ. Two parity bits + 1 message bit = 3 differing bits in the encoded message. If $@ x $@ and $@ y $@ differ by 2 bits, then at least 1 parity bit will still differ. One parity bit + 2 message bits = 3 differing bits. If 3 or 4 message bits differ, then the Hamming distance is again 3 or 4.

Because the Hamming distance between any two encoded messages is at least 3, the Hamming balls around each message have radius at least 1.5. This implies that if a single bit flip occurs, the Hamming distance between the true message and corrupted message will differ by only 1 - thus, the original message can be reconstructed. We find ourselves in the exact situation illustrated in the figure above.

So in principle, to decode the message, one need only enumerate every possible valid encoded message (there are 16 of them), compute the Hamming distance between the corrupted message and the valid ones, and choose the valid message for which this distance is the smallest. Computationally that is extremely unpleasant, but fortunately Hamming came up with a much better decoding scheme (see the wikipedia page on the topic for details).

Human checksums

Now let us consider the puzzle of applying this scheme to human computation.

Suppose we ask a human to perform the following binary computation task:

Blond (0) Brunette (1)

(Sorry Gingers, I'm trying to keep the explanation simple. In a binary world, you don't exist.)

If we attempt to blindly apply the Hamming code, or most similar coding schemes, we come up with a problem very quickly. Suppose our Mechanical Turk has given us a set of 4 tags - [blond, brunette, brunette, brunette]. These tags represent the Turk's opinion about the true value of the message. But unfortunately, to compute a parity code or checksum involving Daenerys Targaryen's hair color, we would need to know it's true value rather than merely the Turk's opinion of it.

This is the fundamental problem - information theory is primarily about encoding a correct message and transmitting it over a corrupted channel. In the mechanical turk scenario, we are taking an erroneous message and transmitting it over a reliable channel (namely the internet).

This is the initial conclusion I came to after thinking about Panos' blog post.

But then I started thinking about my previous work experience at a company which employed mechanical turks. At that point I realized this conclusion is wrong. Mechanical turks can compute some limited checksums and parity bits. I've actually done this extensively in my previous employment - I simply didn't think of it in this language.

To categorize items, we would give workers a categorization radio button exactly like what I display above. But as a separate task, a different worker would compute the checksum. The checksum is computed as follows.

First, we group the items based on the human assigned tag. Then, rather than asking the Turk to tag each item, we simply ask whether the tags are correct:

Yes No

This is a human checksum. The mechanical turk is returning a single bit which represents the correctness of a collection of other bits.

In principle, for many types of human error, the checksum turk should be statistically independent of the turk who performed the initial tagging task. If the tagging turk clicks incorrectly due to a mouse positionining error, boredom or the like, there is no reason to expect the checksum turk to make the same error. The only place we would expect the turk's errors to be correlated is in difficult cases - a dirty blond or a woman with auburn hair, to follow the example I'm using here.

So the answer to Panos' question is yes. You can use checksums and other techniques from information theory to improve the accuracy of a mechanical turk. In industry, we already do a limited version of this - we just don't describe it in information theoretic terms.