Back in my days as a physicist, my Ph.D. adviser came to me with a proposed theory. He wanted to study the many-body Schrodinger equation - to study the interaction of a single charged particle with a conductive screen. I didn't like this theory very much - it offended my sensibilities, and I certainly didn't want to write code to simulate a theory I didn't like. So I made the following reply:

In the end, the world is a lot more complex than making a few assumptions and simulating them. If it was that easy, we'd do nothing but that. The reality is that the complex web of interactions mean that quantum mechanics is difficult to simulate or reduce, and it is chaotic (in the mathematical sense). There have been many well intentioned theories that seemed to be founded in common sense employing models just like yours, that fell flat, for entirely unintuitive reasons once in contact with reality.

It was also very satisfying to say - I felt very smart acknowledging the complexity of the world. By positioning myself as someone who recognizes complexity, I felt almost as smart as if I understood it.

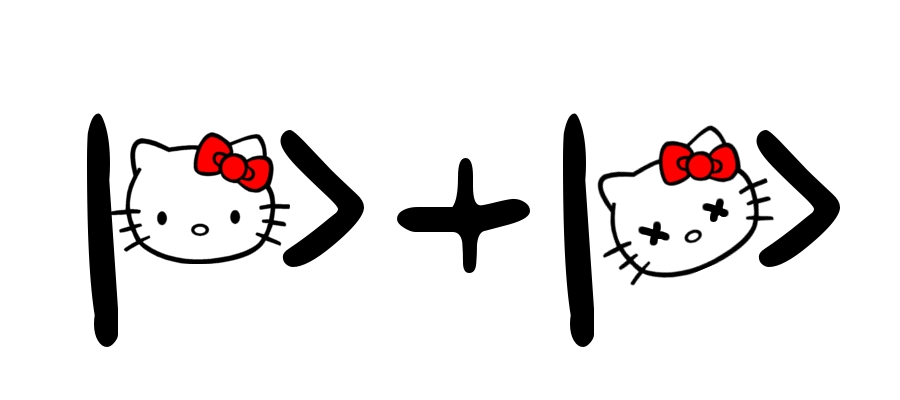

Eventually we came to some agreement, and cooked up a fairly different theory. It looked nothing like his original theory. We eventually came up with a presentation and submitted it to a quantum mechanics conference. They sent us this in reply:

Anytime a talk is submitted to a conference such as this; that is, with explicit references to many body physics and quantum mechanics, I cringe as I read it. It's both predictable, and utterly devastating. Psychology is largely at play here, since cognitive dissonance has extremely strong effects. For the most part, the authors often seems to be completely unaware of the daily realities of a small scale particles. I've lived a macroscale life. But not all particles are macroscopic. I could not possibly comprehend the behavior of life on the Angstrom scale.

Our talk was rightly rejected.

When I want to reject a theory, arguments such as these are a very satisfying way to do it. And one of the best parts of this complexity argument is that it it always works. Any theory can be rejected on this basis outside of fundamental physics.

Of course, that's all ridiculous and it never happened. Physicists don't say things like this. It's an everyday occurrence to take a complex 10^23 dimensional system, reduce it to 3 dimensions, do some simple calculus and draw a (sometimes correct, often illustrative) conclusion.

The quotes above are, however, only slightly paraphrased versions of comments I've seen in other locations and on non-physics topics. They are both examples of a logical fallacy I've made a number of times, and which I've seen others make. I call it the Complexity Copout.

The Complexity Copout

The complexity copout is, stated clearly, the following argument:

System X is complex. Your theory is simple, or at least less complex. Therefore your theory is wrong.

Claims like these are very rarely made in physics or other natural sciences - reducing complex systems to simple theories is done everyday there. But they are often made in the social sciences, business, and in everyday discussions. Someone has a theory of intelligence or economics that I don't like? The world is too complex! A statistical ensemble of human brains are made of 10^27 or so atoms, how can we possibly model such complexity?

Another idea along the same lines:

People are irrational - the science of behavioral economics shows this fairly conclusively. You can't adequately address social issues with reason.

A somewhat equivalent idea, which I've also heard even in the sciences:

The world is random. You can't make good decisions with a deterministic algorithm.

The general claim is that if a system posesses a property, then theories about it or strategies to evaluate it must possess the same property. The most common application of this I've seen in everyday discussion is with complexity, but the same claim is made about randomness and rationality.

Why it's wrong

Let me address first the idea of using randomized strategies to attack a random world. Suppose I have a random process - a loaded coin which comes up heads 70% of the time and tails 30%. The "intuitive" random algorithm to bet on this coin is to bed heads 70% of the time and tails 30%. That strategy has a payoff of 58%. In contrast, the stupid deterministic strategy of always betting heads has a payoff of 70%.

The fact is that to evaluate a strategy, one must look at it's payoff. Measuring how much the strategy seems intuitively similar to the world. Sometimes a deterministic strategy is optimal, sometimes a random one is. Philosophically, I tend to to agree with Eliezer Yudkowsky, who argues that in principle a there are no gains from randomness. But the fact of the matter is that many random systems are best optimized with deterministic strategies.

Similarly, the fact that a system may be complex does not mean that simple approximations can't work. Thermodynamics is a fairly simple explanation of a 10^23 particle system, yet it works well. The Gross-Pitaevskii equation is a 3 dimensional model of a 3x10^23 dimensional system, and it also works well.

If one wants to show a theory is wrong based on complexity, one must show that it cannot explain some specific real world phenomenon. If a theory predicts a uniform outcome but the world is variable, then the theory is too simple to work. But that's a result based on the predictions of the theory, not the mechanics of it.

As an example of this, I used to hold a theory that the primary reason real estate prices were rising in major cities was due to an inability for construction to keep up with population. It was then pointed out to me that London has a decreasing population but increasing prices. That's complexity, but it's complexity that my theory failed to explain.

tl;dr; A lack of complexity in a theory is not a reason to reject it. Only a failure to explain real world phenomena is.