I've recently purchased a Nexus 6p phone. It's a pretty sweet device - it's the first phone that actually fits in my larger than average hands. One thing I really don't like about it is the compass; when I'm using google maps to navigate, the compass will regularly point in the wrong direction. When Android discovers this, it annoyingly asks me to wave my phone around like in the image above.

When the compass is miscalibrated, the direction it points isn't random, however - it's predictably wrong relative to the direction I'm actually pointing it. I.e., if I'm facing north, the compass will point east. If I'm facing south, the compass will point west. In general, at least on a given day, if I'm pointing in a direction $@ \theta $@, the compass on my phone will reliably point in a fixed direction $@ \theta + b $@.

Rather than waving the phone around, wouldn't it be great if the phone could figure out it's own direction based on observing how I walk?

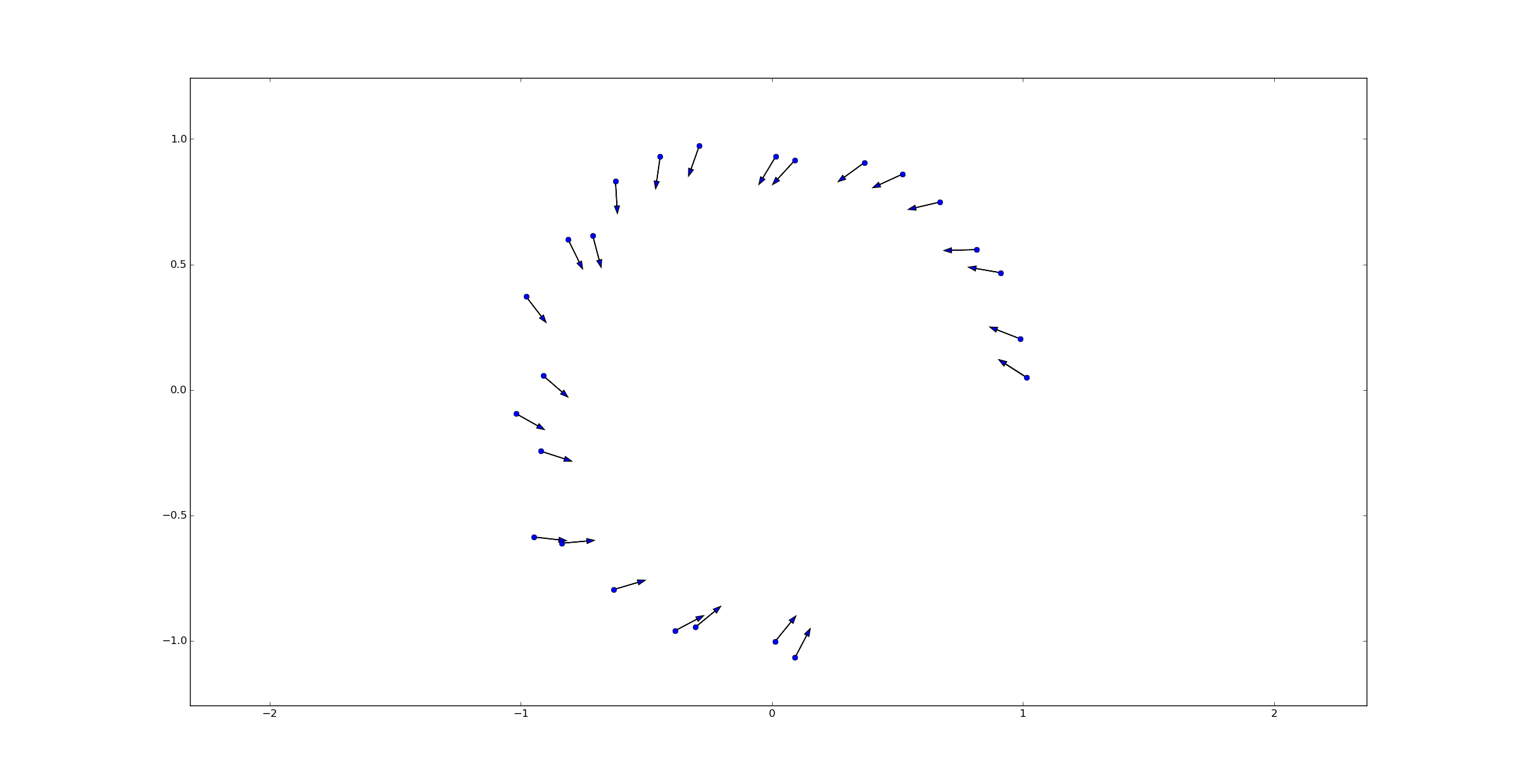

The basic idea is the following. Suppose the phone measures my position and compass to follow roughly the following trajectory:

In this picture, the blue dots represent the measurements of my position while the black arrows represent the direction my compass points - in this case, the directions are off by exactly 1 radian. To correct this bias, we would merely need to rotate the compass displayed on the screen by exactly -1 radian. This would yield a better user experience.

Of course, using simple differencing between positions to measure my direction is not exactly right. Although the data was simulated based on the idea that I was walking in a circle, the noise in measuring my position makes using simple differences between two points inadequate. For example, the arrow from the second to last point (at the bottom of the circle) and the last has an angle of roughly $@ -\pi/4 $@, when it should be pointing at an angle of $@ 0 $@.

On the other hand, eyeballing this picture tells us exactly what the right answer is. Using Bayesian statistics, we can translate this rough intuition into a straightforward algorithm. We can use our position measurements to approximate our direction, and then adjust the compass to match. In this post I'll explain how to do that.

The Model

The model is a fairly simple one, taking place in discrete time.

I'm holding my phone while walking, and I'm pointing the phone in the direction of my movement. At time $@ i = 1, 2, \ldots $@, let $@ \theta_i $@ denote the true direction in which I'm pointing my phone. However, this true direction is not actually observable; instead, at each time $@ i $@, the compass sensor instead reports a measurement $@ \theta^m_i = \theta_i + b $@. Here, $@ b $@ is the error in calibration, and we assume it remains constant in time.

Now lets assume I'm walking at a fixed speed $@ s $@. I start at a position $@ \vec{x}_0 $@, and at time $@ i+1 $@ my position is

However, due to the vaguaries of GPS, I don't actually have accurate measurements of my position. All I get is a noisy set of measurements, namely:

where $@ g_i $@ is a gaussian random variable with mean 0 and variance $@ \sigma^2 $@.

(These unrealistic assumptions, such as walking at a fixed speed, can certainly be relaxed, but I'm trying to keep things simple.)

Probability theory

In Bayesian statistics, we represent our degree of belief about what value $@ b $@ can take via a probability distribution. In this exercise, we'll just use an explicit grid of values to represent this probability distribution. In mathematical terms, we know that $@ b \in [0, 2\pi) $@.

In code terms, we'll have a grid represent possible values of $@ b $@:

b_belief = ones(shape=(1024,), dtype=float)

b_belief /= b_belief.sum()

So in this case, we are considering possible values \(@ b=0 \cdot 2\pi/1024\)@, $@ b = 1 \cdot 2\pi/1024 $@, $@ b = 2 \cdot 2\pi/1024 $@, $@ b = 3 \cdot 2\pi/1024 $@, etc.

At the start, each possible value of $@ b $@ has equal probability, namely $@ 1/1024 $@.

Now suppose that we've gained two position measurements and a direction measurement. How can we use Bayes rule to update our beliefs? Bayes rule tells us that:

What we need to do is compute $@ P( \vec{x}^{m}_{i+1}, \vec{x}^m_i, \theta^m_i | b) $@. Once we have this value, we can (for each value of $@ b $@) change our belief.

Note first that $@ \theta^m_i = \theta_i + b $@, so $@ \theta_i = \theta^{m}_i - b $@. Note also that $@ x_i = x_i^m - g_i $@.

Plugging these two equations into the definition of $@ \vec{x}^m_{i+1} $@ yields:

Rearranging this yields:

Since $@ g_i $@ and $@ g_{i+1} $@ are both normally distributed random variables, their sum (or difference) is a new normal distribution:

So we can now use this to compute $@ P( \vec{x}^{m}_{i+1}, \vec{x}^m_i, \theta^m_i | b) $@. In code:

def update_belief(delta_pos, measured_dir, prior):

dist = norm(0, 2*sigma2)

posterior = dist.pdf(delta_pos[0] - cos(measured_dir - theta_grid)) * dist.pdf(delta_pos[1] - sin(measured_dir - theta_grid))

posterior *= prior

posterior /= posterior.sum()

return posterior

Here, the variable delta_pos represents $@ \vec{x}^m_{i+1} - \vec{x}^m_{i} $@ while measured_dir represents $@ \theta^m_i $@.

Results

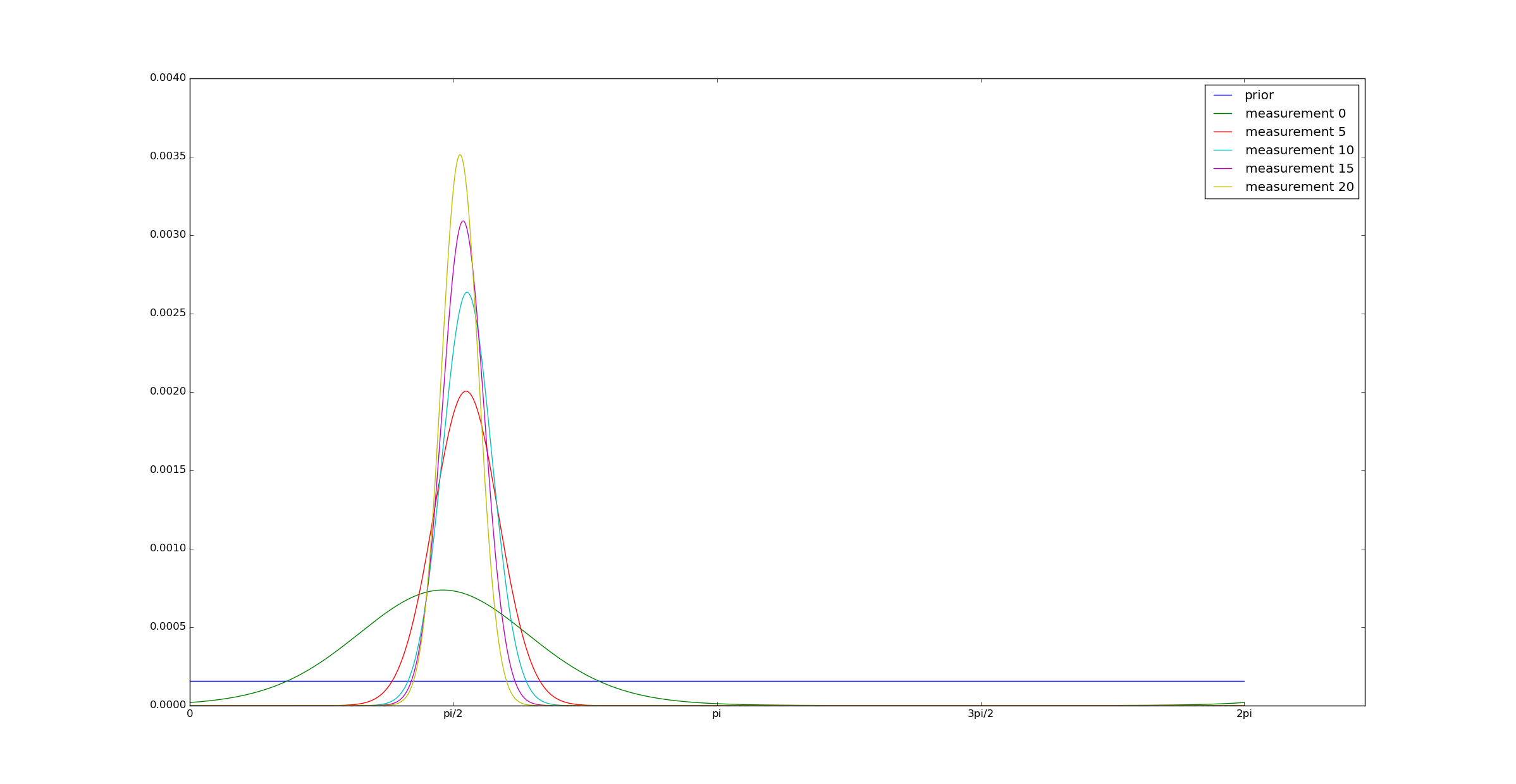

To test this algorithm, I generated synthetic data to test this algorithm. I generated motion along a random trajectory, and a sequence of observed trajectories. I imposed a bias to the compass of $@ \pi/2 $@, and then computed a posterior on the bias using the above algorithm:

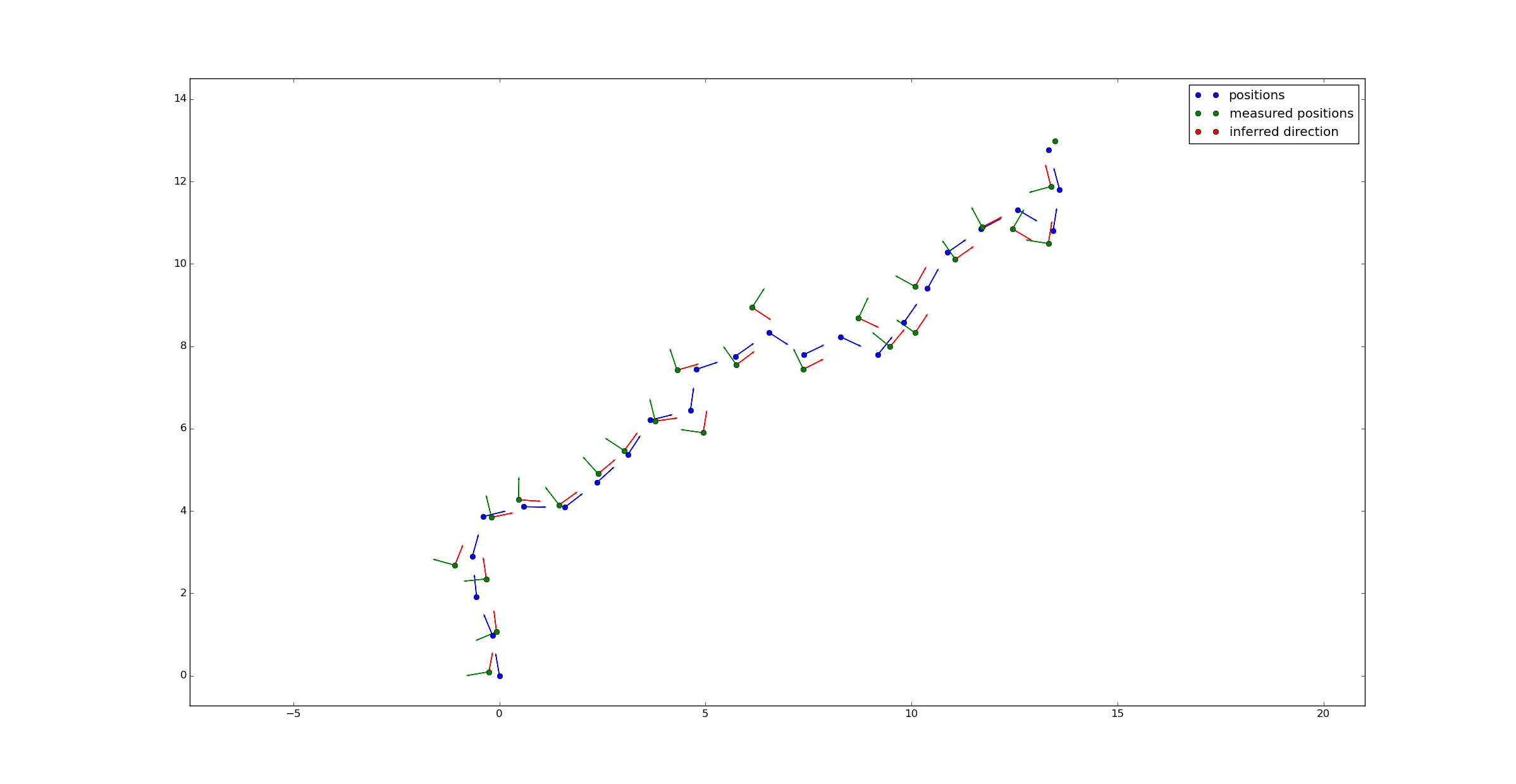

If we display the average direction (as per the posterior) on a map, we get accurate directions after a few position measurements:

Full code is on github.

As can be seen from the graph, the algorithm converges reasonably rapidly (after 5-10 measurements). So this means that after walking far enough for the GPS to make 5-10 distinct measurements, my phone can approximately calibrate the compass, certainly enough to be usable.

So google, I love your phone. It makes me happy. But could you consider improving the compass calibration, do the work for me so I don't have to wave it around like an idiot?